YB Yeats – The Second Coming (1919)

Turning and turning in the widening gyreThe falcon cannot hear the falconer;Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhereThe ceremony of innocence is drowned;The best lack all conviction, while the worstAre full of passionate intensity.Surely some revelation is at hand;Surely the Second Coming is at hand.The Second Coming! Hardly are those words outWhen a vast image out of Spiritus MundiTroubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desertA shape with lion body and the head of a man,A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,Is moving its slow thighs, while all about itReel shadows of the indignant desert birds.The darkness drops again; but now I knowThat twenty centuries of stony sleepWere vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

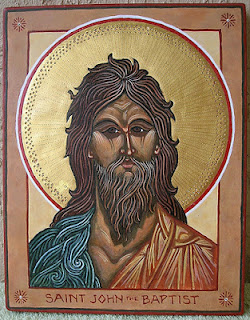

|

| Greg Weatherby 'Birth of Jesus' |

And then there’s the pandemic. Not the Spanish flu this time, but Covid-19. To date Covid-19 has killed 1.8 million people and sent the global economy into its worst recession since the early 1930s. The disease has been cruel in the choices it forces upon both governments and individuals. Some have continued to work, to keep their businesses open, to meet with friends and family in the same way as we’ve always done. The cost of this choice is very often contracting the disease and passing it on; many who chose this path have died. The other choice is not so good either, really. To stay at home, to cease working in the social way we have been used to, to stop meeting up with friends and family in order to slow the progress of the disease through the community. But, for many, embracing this second set of options – often in the name of caring for others – has unleashed unprecedented levels of loneliness, isolation and, for some, a life and death struggle with that equally merciless killer, depression. To avoid one kind of pandemic, it seems, many of us have had to throw ourselves into the path of another.

Climate change. Pandemics of body and mind. We could go on to consider the impact of these things on the refugee crisis, the plight of Indigenous peoples, international students, casual workers and so on. We could talk about Trump and Sco-Mo and Boris, we could talk about populism as a symptom of anxiety. But I will refrain. You get the point. There’s a lot of anxiety out there, and the anxiety is not a response to things that aren’t actually there. There are very good reasons to feel anxious. There are good reasons to believe that the centre can no longer hold, that the order of things we have come to take for granted is about to go belly-up. Very good reasons.

I want to point out, however, that when Yeats wrote his poem in 1919 he conveniently forgot a few things. He forgot that the British has been brutalising and starving the Irish for several centuries already, and that the prospect of a new crackdown on the independence movement was therefore hardly unexpected. He also forgot that the Great War was not the first conflict to have devasted Europe. It was simply the latest in a continuous series of conflicts that had already killed or maimed millions and destroyed economies utterly. Hardly new. He also conveniently forgot that the Spanish flu was not Europe’s first pandemic. There had been plagues and 'black' deaths for centuries. Again, hardly unprecedented. All of which is to say that whilst Yeats brilliantly captures the anxiety he felt in 1919, his poem can hardly be taken as a witness to something entirely new or unforeseen in the story of humanity.

Quite simply, there has never been a ‘centre’, some kind of cosmic or moral order, that is suddenly falling into rack and ruin. Rack and ruin has been the name of the game from the beginning. There has always been war, there have always been bully-boy politicians, there has always been poverty. There has always been illness and death. At the time when Jesus was born, for example, the Jews had been ruled by foreign powers for three centuries already. They knew well that everything had gone to pot. The life-expectancy of your average landless male peasant was around 30 years, and just 40 years if you happened to have a trade, such as carpentry. Most of the Jewish population now expected that life would be short, and it would be brutal. You were born, you worked yourself to the bone to keep your family from starving, and then you died very young, and usually left a widow but hopefully some sons and daughters who could take over the family business and do it all again. To a family like that, just like that, Jesus was born.

It’s easy to give into despair. Very easy. Most days, especially in the lead-up to Christmas, I am sorely tempted to go there. Afterall, my own people were colonised by the British and felt the savagery of the moral 'order’, the ‘centre’ they wished to impose. I still carry the trauma of that in my mind and my body. So, too, this stolen ‘country’: our lands, seas and waterways. There are deep wounds in our dreaming-places wherever you turn. But I don’t go there: to despair, I mean. And the reason I don’t is actually very simple. I believe that in spite of all that is wrong, there is a power in the world for right. That is spite of all that is brutal and cruel, there is a power in the world that is caring, and knows how to offer love and succour to all who are hurting. I believe that in spite of the darkness and ignorance that floods our country and our lives, that there is a power in the world for light and life, and for living with country as kin, as family. That this power is here with us - that it is all around us, that it waits patiently to seep into our minds and hearts at the first indication that we are willing and in need - I can never prove to anyone. Not in the unassailable manner that many expect, anyway. But I can testify to its reality, to its power, and to its essential character: love, kindness, welcome, shelter, hospitality. I see and feel and know these things every single day.

Rather than rabbit on and on and on about love, and about Jesus as the way in which love shows itself to the world, I want to read another poem: a poem, this time, from a humble parish priest from the Welsh countryside, a place somewhat subaltern to the English seats of power.

RS Thomas - The Coming

And God held in his handA small globe. Look he said.The son looked. Far off,As through water, he sawA scorched land of fierceColour. The light burnedThere; crusted buildingsCast their shadows: a brightSerpent, A riverUncoiled itself, radiantWith slime.On a bareHill a bare tree saddenedThe sky. many PeopleHeld out their thin armsTo it, as though waitingFor a vanished AprilTo return to its crossedBoughs. The son watchedThem. Let me go there, he said.

The Son did come here, to live amongst us, to teach us his way of love, and to save us from the worst excesses of our inhumanity and hatred of country. It is that coming, the coming of light and love and kindness and compassion, that we celebrate tonight, and to which we commit ourselves anew for a more hopeful future.

I wish you all a holy and most joyful Christmas.