Isaiah 35.1-10; Magnificat; James 5.7-10

The letter of James, which we read just now, says:

Be patient, therefore, beloved, until the coming of the Lord. The farmer waits for the precious crop from the earth, being patient with it until it receives the early and the late rains. You also must be patient.

This morning I want to speak a little about what it might mean to be patient as we wait for the coming of the Lord. For quite clearly, the Lord has not yet come. Not in his fulness, not to transform the world and human community into the image of God’s lovingkindness. For if the Lord had already come in that way, we would not need to pray our prayers of intercession. We would not need to sing the Magnificat, the Song of Mary, as we do this morning and at evening prayer. The despots would already have been removed from their thrones and the poor raised up. The rich would already have been sent away empty, and the hungry filled with good things. The swords would already have been beaten into ploughshares, and we would be at peace.

That this is not the case means, quite simply, that the messiah has not yet come. On that, and many other things, Jews and Christians are agreed. So, what are we to do in the meantime? What are we to do as we wait for the crops of justice to grow, as both Isaiah and James imagine? What are we to do whilst we wait for our hope to be realised?

Well, according to St James, there are two things we can do.

The first, he says, is to stop grumbling against one another: to stop judging one another. For, that is one of our finer skills as Christian people. Do we not look across the desk or the table or stare into our screens that those we disapprove of, and do we not ruminate upon the ways in which those people are unworthy, somehow, of love or affection? For all the problems in the world come from other people, do they not? Surely Jean-Paul Sartre was right when he said that ‘hell is other people’! If only they were not around, we could fix things! If only they were not around, the world could be put to rights! We imagine, do we not, that when Christ returns it is they who will get their comeuppance, whilst we, the truly good and righteous people, will be received into the divine halls? Or perhaps it is only me who thinks that way. Perhaps it is only me who needs to hear the divine command ‘judge not, lest you be judged’. But more of that later.

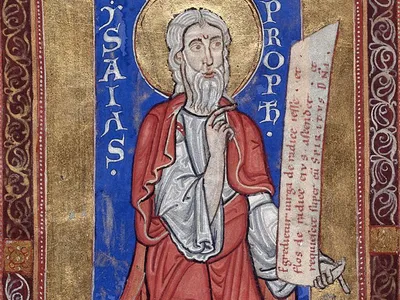

The second thing James says that we can do whilst waiting for Christ is to suffer patiently like the prophets. Which is something of an oxymoron. At least it appears to be. For the prophets, on my reading, were rarely patient. Indeed, one might more accurately describe them as paradigm examples of the impatient! They were impatient about the abuse of power, they were impatient about hypocritical religious types, they were impatient for the liberation of the poor and the raising up of the marginalised. And they expressed their impatience and frustration loudly, and in the places where they were most likely to cop a beating for their trouble. So, what’s patient about that? A fair question, I reckon!

The kind of patience we are called to exercise as Christians is not, in fact, a ‘quietist’ kind of patience, patience understood as a meek and mild acceptance of all the wrongs in the world, as if there is nothing we can do to change things. For, if the harvest of justice is to arrive, we are called to be farmers and horticulturalists, that is, people who not only wait for the seed to grow, but also work hard to prepare the soil, and plan meticulously to ensure that the most optimal growing conditions are in place. I have never met a husband of the land – least of all amongst mob – who sits back and does nothing when there are hungry mouths to feed. For us, the care and nurture of the land remains a daily responsibility. For, to our way of looking at things, if we do not tend the land with loving care then we should not be surprised or angry if the land fails to be fruitful. If the land is to be fruitful, it should be tended. Carefully, and with unhurried patience.

So it is with the friends of God and the prophets of this current age. If justice is to arrive, we must work at it patiently. If Christ is to arrive, then we must sow the seeds of justice with sobriety and regular, even ritual, attention. Which is precisely what Christ did when he came around the first time. He went amongst the villages of Galilee giving sight to the blind, mobility to the lame, hearing to the deaf and belonging to the poor and excluded. All of which can be understood as a sowing of seed, a preparing of the ground. Because not all were healed, not all found themselves welcomed back into community. Not all were raised to life. What was done was a sign and a promise of what is yet to come: justice and healing for all. But now it is our turn. It is the special calling of the church to become these signs anew, in our community and in our politics. It is we who are called to tend the land and sow the seed. It is for God to make the seed grow and bring the harvest to fulfillment. But we each have our part in preparing the way.That’s all well and good. But still I am troubled by a question, a question that hides between the two instructions James has left us, a question that hovers between the injunctions to ‘stop judging’ and ‘suffer patiently like the prophets’. And it’s this: how can we name what has gone wrong, and work towards a more just alternative, if we are never allowed to judge other human beings? Is it not human beings who commit the crimes? Is it not human beings who make the policies that result in persecution, harm, and even death for vulnerable populations? Is it not human beings who exploit the earth and render it uninhabitable in so many places? How, then, can we be prophets who cry out for justice if we can never judge our fellows for their crimes?

You will perhaps understand how I might struggle with this question as a trawloolway man, an Aboriginal person, a member of that people against whom much wrong has been done, and continues to be done.

Well, the way I see it (and I’m happy to be corrected) is that we are called to ‘hate sins, but to love humankind’ as St Augustine put it in one of his letters. We can work against what people do to harm the earth and each other, in other words, but this does not require us to condemn the people who do it to hellfire and damnation. The scandal of the the gospel is that no-one is beyond the love and mercy of God. All are loved, even if what they do is evil. And that goes as much for Hitler, and Pol Pot, as it does for the thousands of good churchmen who massacred our people. We must work as hard as we can to discern how evil is present, and to limit the effects of that evil in our hearts and in our world. But we simply do not have the authority to pass final judgement on any human being, least of all ourselves. That is something for God alone. So we should leave those matters to God. We are not called to respond to hate with hate, but to love our neighbours as Christ has loved us.

So, allow me to summarise what James encourages us to do whilst we wait for Christ to arrive. Don’t judge or condemn anyone, lest you yourself are condemned. And work for justice with the patience, and love, and consistency of the prophets. If we do these things, we will have done our part. The rest is for God, and for the Christ who will come to recast the cosmos in the image and likeness of divine love.

Garry Deverell