Texts: Malachi 3.1-7; Luke 2.22-38

When Jesus is taken to the temple in Jerusalem to be dedicated to the purposes of God, Luke has an old man named Simeon say the following prophecy over the child:

Now my eyes have seen your salvation you have placed in the midst of all peoples, a light for revelation to the Gentiles and for the glory of your people Israel . . . This child is destined for the falling and rising of many in Israel. He will be a sign to be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed . . .

Here the venerable Simeon appears to recall the prophecy of Malachi, who imagines the Lord

. . returning to his temple. But who can endure the day of his coming, who can stand when he appears? For the Lord is like a refiner’s fire, like fullers’ soap . . . I will be quick to bear witness against the magicians, the adulterers, the liars, the oppressors of workers, of widows, orphans and aliens, again those who do not fear me, says the Lord.

By this Luke foreshadows three themes that will become very important in his gospel as the story unfolds. The first is about the identity of Jesus as God’s messiah. The messiah, he says, is like a very bright light in the world, a light with such glory that everyone’s secret agendas (whether for good or for evil) will be penetrated and revealed for what they are. The second theme takes the form of a paradox. Though the light of the messiah is very bright, not everyone will see or understand what his light signifies: forgiveness, salvation and peace for all. For many, his light will be a threat. They will name it ‘evil’. They will do everything in their power to oppose and extinguish its power. A third and final theme, and the one that concerns us most this morning, is a question that Luke’s text will always ask of its readers: what shall you do with this Christ? When the light reveals your own secret thoughts and agendas, will you allow God to forgive you, to free you for salvation and peace? Or will you oppose and deny and obfuscate until the end?

So, let us examine each of these themes in a little more detail.

First to the idea of Christ as a sign or portal of God’s light in the world. There is a long tradition in Israel of thinking about God as a very bright light. It begins, apparently, with the story of the Exodus. There God is consistently seen as a pillar of light that guides the Israelites from the darkness of their slavery in Egypt to the brightness of their freedom in the 'promised land'. There is also a long tradition that associates the flame of God’s glory with certain human beings, those who take a lead role in the people’s salvation. Moses’ face, we are told, glowed with God’s glory every time he returned from conversation with Yahweh. Out of these traditions grew a view that the Hebrew messiah, when he came, would be like a sign or portal of divine light in the world, a conduit by which the light of God’s glory would be let loose to free everyone who walks in valleys of darkness or despair. We read some of those prophecies a month ago when we celebrated the birth of Jesus. So it is by this route that we come to Simeon’s prophecy over the infant Jesus, that he shall be the glory of the Hebrew people and a light for all peoples everywhere. Jesus, Luke tells us, will be the messiah in this specific sense: that he will save the people from their sins, that is, from everything that keeps them in a state of slavery.

But this takes us immediately to the central paradox in Luke’s gospel. If the Christ is born a divine light to the gentiles and the glory of his people Israel, how is it that this light is apparently unrecognised by so many? Why is it that so many oppose him from the beginning, and eventually have him killed? Why do they not see who he is, why do they not fall down and worship him? Luke’s answer is both literary and theological. ‘Don’t take the metaphor of the light too literally’, he says, ‘for the light of Christ is a very different kind of light than you are used to thinking about.’ It is not the light that we human beings make for ourselves: it is not the glory of our kings and rulers, or the translucent beauty of the human body so celebrated in the sculpture of the Greeks. Neither is it the light that accompanies everyone who fulfils the law of their community or culture, so that everyone looks to them as paragons of virtue or success. No, the light of Christ is rather different. It is an uncomfortable kind of light, a light that penetrates into dark places that are usually kept secret. It is an ultra-violet kind of light, that glows with a subdued intensity to show up both the dark stains in the heart of those the world would look to as glorious, but also the hidden purity of those the world would dismiss and scorn, those who look to the grace of God, alone, for any sense of light or virtue.

The light of Christ is, first of all, a light of uncovering or revelation. It exposes and makes manifest the truth of our humanity and our inhumanity. That is why it is the the poor and the desperate who first recognise the light of Christ. These are people who know full well that our lives are broken. They know full well that no matter how hard we try, very few are able to generate lives of apparent success and bathe, thereby, in the light of social and cultural approval. In Christ we hear the word of God’s love and welcome. In Christ we learn a way to live with generosity and joy, free from the norms of success or failure generated by our societies. In Christ we learn how to live as though all that mattered was the mercy and kindness of the divine. And so we learn to practise mercy, to give ourselves away as though nothing could possibly be lost in doing so.

But the many others, those who refuse to recognise Christ’s light, are nevertheless exposed by that light. In our clinging to the dominant norms of self-generated power and success, in our opposition to Jesus’ preaching about God’s preferential love for the poor and the powerless, we are shown up for who we are: people who were slaves of society and of fashion and of conventional morality, people who are unable to see that, in fact, it is the rich and powerful who are truly poor, standing in the most desperate need of divine mercy.

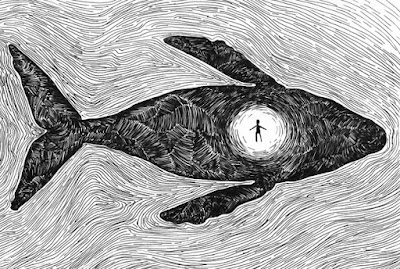

The light of Christ is revealed most surely, Luke tells us in chapter 11 of his gospel, under the paradoxical sign of Jonah. In his temple blessing, Simeon said that Christ would be a ‘sign to be opposed’. In chapter 11 we learn what this most offensive of signs is: that, like Jonah in the belly of the fish, the Christ would lie dead in the earth for three days but would then rise as a sign that God had vindicated his cause. The message of the parable is a scandal, a stumbling block for any who believe that the way of the messiah is that of power-over others, rather than power-for-and-with others, for anyone who looks to God for confirmation of their greedy and indifferent lifestyles. For at its heart the sign of Jonah speaks of the willingness of God’s offspring, out of love for the world, to journey into the belly of empire where there is every prospect of being consumed. Yet, finally summoning his courage, this Jonah-Christ figure speaks the truth and survives. Just. Marginally. For speaking the truth in the belly of empire can very easily end in death or, at the very least, expulsion. The sign of Jonah is therefore double-edged. It tells us that the way of God in the world is that of love and grace and the sacrificial telling of the truth. But it is also a sign of judgement on all who choose to ignore that truth and reject the mercy on offer.And so, finally, we come to the question Luke asks of his readers: what shall you do with this Christ? When his light reveals your secret thoughts and agendas, will you allow God to forgive you, to free you for salvation and peace? Or will you oppose and deny and obfuscate until the end? ‘Obfuscate’ is a big word. It means ‘to cover up’. There are some who are privileged to hear the word of Christ and experience the enlightenment he brings who then choose to take up their cross and follow him, beginning always with recognition that they will never be truly free apart from divine mercy and help. But there are many who hear Christ’s word and experience his light who then choose to obfuscate or cover up the truth that light exposes because, deep down, they are in denial of the truth and their whole lives are lived according to the logic of a lie. What this lie amounts to, in the end, is an attempt to remake the world in the image of the unredeemed human heart, mistaking darkness for light, evil for good, and slavery for freedom.

That is how we get to the absurd situation we are in at present with ‘Australia Day’, for example. It is as though the whole nation is living in la-la-land, determined to celebrate itself as a place of peace and freedom when, historically, January 26 signifies nothing other than end of peace and freedom for those of us who were already here when the British arrived. And the beginning of what can only be described as a totalitarian annexation of Indigenous land and life under the twin signs of genocide and ecocide. Australia Day is therefore a parable about the very essence of sin. It is about the denial of the truth of who we are before our creator. I submit to you that until we can tell the truth about our ourselves as a nation, and seek to make meaningful amends, we shall forever exist in a state of arrested development, of national adolescence. Wanting to be grown-up and responsible, yet unable to do so because of our continuing penchant for fantasy and self-deception.

So what will you do with this Christ, this bringer of truth? When his light shines on your world and in your heart—on the way you do your business, on the behaviour that you model for your children and grandchildren, on the things that you treasure more than anything else in the world—what will you do? Will you cover up the truth and oppose it? Or will you fall at Christ’s feet and beg for his mercy, his peace, and his joy? I promise you, that if you choose the latter, if you are willing to lose everything for the sake of the gospel, Christ will take you in his arms and give you a future hitherto unimagined, a future that shares in the sovereign inheritance of all God’s children. But if you refuse his light, whether as an individual, a community, or a nation, you will reap only what you have sown: a whirlwind of Darwinian darkness in which the strong cannibalise the weak until all are weak, all are victims, and life is gone entirely.

Like the prophets of old, like Simeon and Anna and Malachi, I put before you the way that leads to life and the way that leads to death. Please, choose life.