Texts:

Isaiah 40.1-11; Psalm 85. 1-2, 8-13; 2 Peter 3.8-15a; Mark 1.1-8

Let

me begin with a story, a might of been, with regard to that voice crying out in

the Judean desert. Down

amongst the ruins that used to be Jerusalem, a voice cried out:

In the wilderness prepare the way of the Lord.

Make straight in the

desert a highway for our God . . .

Then the glory of the

Lord shall be revealed,

and all people shall

see it together,

for the mouth of the

Lord has spoken.

The voice drifted on the morning breeze to where Joseph and Baruch

were cooking their breakfast on a nearby hill.

‘What highway’s he on about?’ said Joseph to Baruch. ‘The highway of the Lord’, said the

other. ‘Apparently God is going to

restore our fortunes. He’s going to come

roaring down this new highway they’re making, rebuild the city, and set up

court in the temple as if he were Moses himself!’ ‘Somehow I doubt it!’, said Joseph, and

their laughter pealed across the valley.

But after the silence had taken hold once more, Baruch said: ‘Still, that’d be nice, wouldn’t it. A king in Zion who’d give blokes like you and me a

go. I’m blowed if I’m going to slave my

guts out to keep these new bloody nobles in their palaces!’

Joseph chewed his tripe thoughtfully. ‘Time for a year of . . . ah, what did they call it? . . . Jubilee,

that’s it. Time for Jubilee, when all

that’s been lost or screwed up get put back to rights. You know, it was the grandsires of these new

bloody nobles that confiscated our clan-land back in the time of Uzziah’. And then his eyes filled with tears. ‘I’d swear my troth to a Jubilee King. Bloody oath I would. Bloody oath’.

The cry of an eagle lifted their eyes to the sun, while, in the valley

below, a shepherd led his sheep through the ruins.

________________________________

‘So who is this Baptist fellow, anyway?’ asked Simon. ‘A hermit’, said Uriah. ‘He comes from a good family, by all

accounts. His father was a temple

bureaucrat and he was being groomed for the priesthood. But right in the middle of his training he

had a bit of a turn and bolted for the desert!

Apparently he spent some time with that monkish crowd out near the dead

sea. What are they called?’ ‘The Essenes’, answered Simon. ‘Yeah.

They’re pretty strange, by all accounts, waiting for their beloved

Messiah to come! My uncle Max (you know,

the psychiatrist who trained in Rome) reckons that these separatist groups

don’t have the ego-strength to mix it in the real world. So they run away to the desert, where they

can set up their own little fantasy.

Makes life simpler, I’m sure. But

it’s such a cop-out. They could never

cope with the real world that you and I know about, that’s pretty clear!’.Uriah took a drag on his cigar and ordered another caráf of

red. ‘I went out for a look the other

day’, he said, casually. Simon nearly

choked on his café-latté. ‘You went out

for a look? My God, man, what possessed

you to do something like that? Surely

you’re not having a mid-life crisis! Not

at the tender age of 35!’. His laughter

filled the restaurant, but Uriah didn’t join in. Flushing, he stared into his drink. Simon stopped laughing. ‘I’m not sure why I went, exactly’, said

Uriah, looking up and out, as if towards an empty sky. Then he turned to look his companion in the

eye. ‘Listen, Simon. This is going to sound weird, but . . . I’m feeling a little jaded right now. This ‘real world’ we live in, you and I,

isn’t feeling like much fun at the moment.

What’s real about being part of the Jerusalem middle-class? Most Jews live in landless poverty! What’s real about doing legal work for the

Romans? They’re the occupying power, for Moses’ sake! I feel like I’m betraying my own people,

stomping on their heads just to get a leg up!

Add to that the fact of my disaster of a marriage! I work so hard that I hardly ever see my

kids, and I really don’t know who Priscilla is these days, or what she

gets up to . . .’

Simon’s face has turned pale.

‘Mate’ he said. ‘I can’t believe what I’m hearing. Listen, life might not be all it’s cracked up

to be at times. But this is how it

is! This is reality! This is reál-politics! God Almighty!

What did that preacher say out there anyway?’

‘”Prepare the way of the Lord”,’ said Uriah. ‘”Prepare

the way of the Lord” . . . that’s

what he said. He was baptising people in

the river to wash their crappy lives away.

And he spoke of a Great One to come who would baptise not with water,

but with the Holy Spirit.’

Suddenly the space around the two men was different. Something shifted, the world changed. Even the sunset and the evening breeze seemed

to speak in a different voice. For a

moment, Simon was caught there. From a

place deep in his people’s history he heard the mad voices of nomads, prophets

and saints, crying out with anguish and longing for a world made new. And for a moment, just a moment, he joined

them in their longing. But he shook

himself free from the reverie, and rose from the table. ‘Uriah’, he said, ‘you’re losing it

mate’. And away he walked. Back to the real world. The world of cafés and credit and weekends at

the beach-house.

_____________________________________

When you come to worship, why do you come? Is it to escape from the real world, to run

away from the awfulness of life? Or is

it the opposite. Did you come,

perchance, to enter, albeit for a moment, a world which is somehow more real, a world that takes your

reality seriously, and addresses you where you are afraid, and hurting, and in

need of healing?

If this Advent season is about anything it’s about taking the

voices that cry in the wilderness seriously, the mad voices of nomads, Indigenes

and saints, the voices that tell the truth.

And what is the truth? Simply

this: that the “real” world is a fake; that capitalism and the mad rush to

accumulate and consume is killing us all, body, mind, and spirit; that entertainment

and celebrity are stealing away our capacity to lives our own lives. Ha! I remember a schizophrenic friend

being afraid to turn on the television.

“When I do,” he said, “the demons suck my spirit away.” I thought he was dangerously unstable at the

time. But now I’m not so sure. Now I reckon he was on to something.

The voice that cries in the wilderness tells another truth

too. “Things can be different,” it says,

“Thing can be different than they are today.

Why? Because the glory of God

is coming! It is on its way, and it

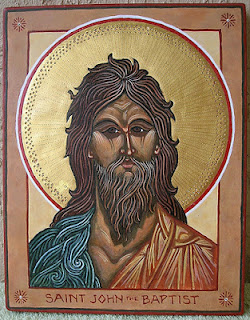

is nearly here.” You see, what John the

Baptist promised people out there in the desert was not just change, but metamorphosis. What’s the difference, I hear you ask? Well, let me put it like this. Change is when you swap from Pears shampoo to

Decoré. Change is when you sell up in

Balwyn and move to Canterbury. Change is

watching “Sixty Minutes” instead of “Today Tonight”. But metamorphosis? Metamorphosis is when a Tootsie family in Rwanda is able

to invite their son’s Hutu killers to dinner.

Metamorphosis is when Senator Macarius of Rome becomes a hermit monk, and plaits ropes

for a living in the Egyptian desert.

Metamorphosis is when the colonist reliquishes power to the point of making treaty with the colonised.

To be metamorphosed. In the

Greek of the gospel the word is metanoia, and it is expressed and

performed in the practise of baptism. In

the early days of the faith, when the church seemed to have more enthusiasm for change than we do today, baptism was taken very, very seriously indeed. For baptism was not just a ceremony of change

designed to welcome people into a church they can neither comprehend nor belong

to. Rather, it was a powerful sacrament

of metamorphosis, a piece of method theatre in which the candidate bound themselves

so intimately to Christ that everything they had been before they heard his

call was literally cast aside in order to make room for the new life which

Christ had promised them by his love and his grace. In approaching the waters, the candidate

would remove their clothes. Then they

would descend, naked, into the waters, where the priest would pronounce the

sacred words. Then, when they emerged,

the choirs would sing and they would put on the new garb of white, which

symbolised the glory of Christ. No

longer would they live from their own powers.

From now on, they were dead, marked with the scars of the crucified Christ. The life they now lived in the body would be

that of the Son of God, who loved them, and gave his life for them. Here there was no gap between ceremony and

life. Life became baptism, and baptism

became the life in Christ.

In baptism we pledge ourselves to Christ, to become his slaves, to

give ourselves into his hands completely.

But in doing so we in respond to a love and promise that always already precedes

our decisions: Christ’s promise to

always be there, on the other side of the waters, there to raise us from the

depths, and array us in the splendour of the redeemed. The promise assures us that our time of

penance is ended, that it is God, himself, to now comes to work the

forgiveness, freedom and deliverance we so long for. Without this promise, all of our being sorry

and all of our determination to change makes for nothing.

In this we find out what Advent really means, as the season of promise

par excellence: that within and beyond

the appalling squalor of our greedy, consumption-driven lives; within and

beyond our self-hatred and despair; within and beyond the awful inhumanity of

our politics; within and beyond all this, Christ arrives. Christ arrives with love enough, with peace

enough, with hope enough to make things very, very, very different.

Glory be to God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—as in the beginning,

so now and for ever, world without end.

Amen.

Garry Deverell